Close Reading Series: Morgan Levine on "Sonnet"

The Close Reading Series invites our board editors to write about a favorite piece from our Spring 2020 issue. These readings are not intended to be definitive interpretations; when we read, we bring with us our own histories, experiences, and references, all of which guide our relationship to the work before us. It is possible, even probable, that the meanings our editors found in these pieces will be different from your own, and perhaps even different from the authors’ intentions. We hope that these close readings will demonstrate what we loved about these pieces, and encourage you to find things to love about them as well.

This week, Editor-in-Chief Morgan Levine discusses “Sonnet.”

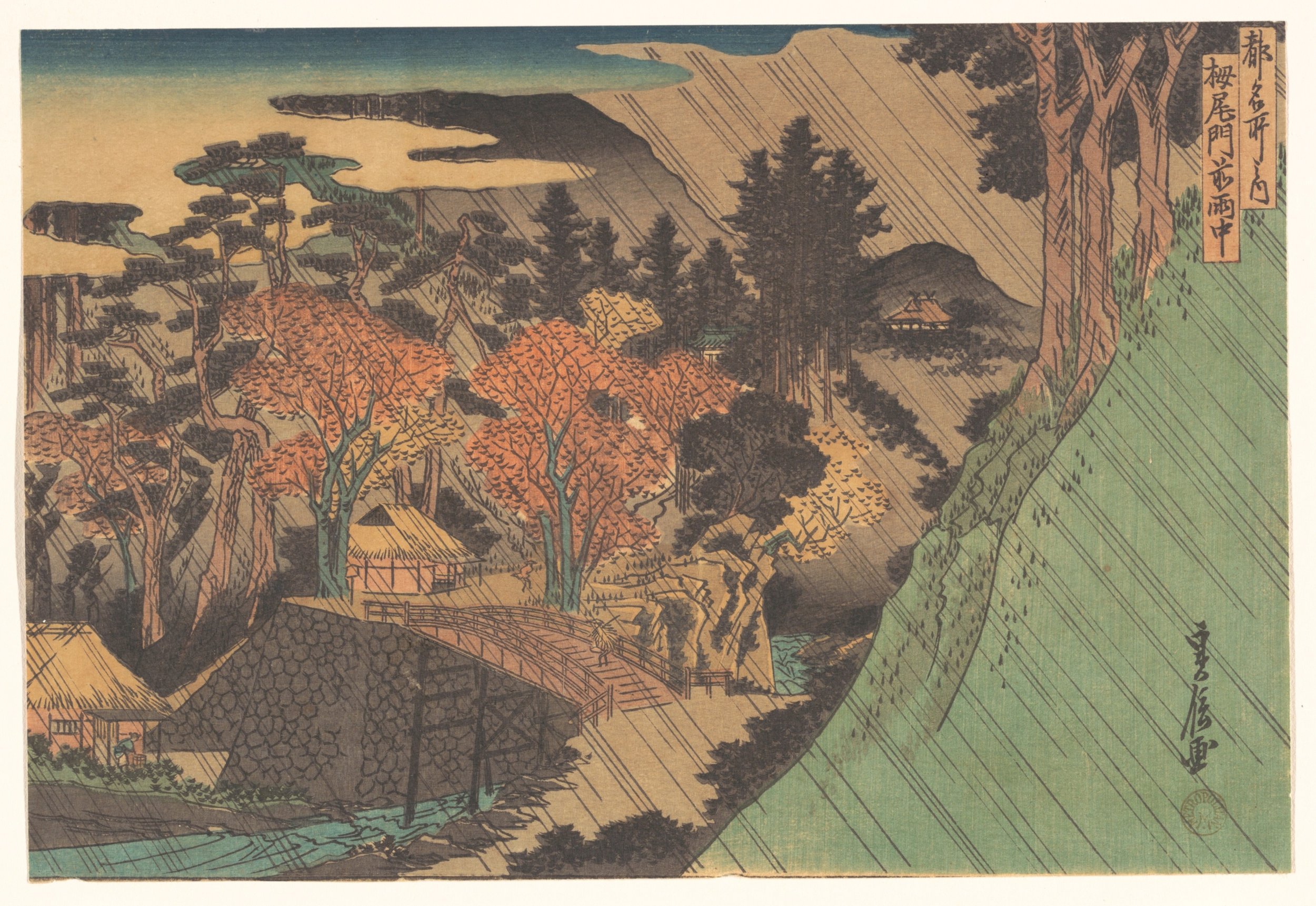

Andrew Stone’s “Sonnet” has come back to me many times since I first read it in January, often while driving, always in the time after sunset when some light remains and the sky is big and denim-colored. There’s something so aching but self-aware about it. To be a sonnet and to name yourself a sonnet, sentimentality and the obviousness of analogy, that’s all here. But there’s also a distinct clarity, which the shortness of the form assists: this is a very specific poem, about a very specific moment -- “6:40pm on Wednesday.”

“Sonnet” is sonically very busy: the sound of rain, the “train horn / like Verklarte Nacht,” the cicadas. It reminds me of Pitchfork’s review of Playboi Carti’s Die Lit: “This is music that fundamentally recalibrates the brain’s reward centers.” However, it also reminds me of the Smog song “Our Anniversary,” slower, older, and humming with the histories of a relationship. Stone twists the thread between sound and meaning: the gobbling cicadas, or “the turkeys of the trees,” is a brilliantly disconcerting description, and I felt it dial a familiar noise into a new shape. Cicadas are ironic witnesses to the past love, “spies / who constellate the vast” -- but the poem sees where it’s headed and sighs at itself -- “vastness.” The vast vastness, the way a sonnet can unfold a moment and refold it with all of its edges revealed.

I think this poem is very intentional in how it dilates meaning. “The door, a door” in particular stopped me, as I watched an object in the poem move from the symbolic to everyday. The rain is romantic, but loves the form of the city rather than the city itself. The ending is a maze I love to trace: the speaker of the poem feels the specialness of this moment out-of-love, a specialness that comes from the moments in-love, and in that moment is enacting love. And so we have another love sonnet, performing itself just slightly off-key. And I love and honk for that.

Read more of our Spring Issue here.

Close Reading Series: Sofia Montrone on "(46)" and "(47)"

The Close Reading Series invites our board editors to write about a favorite piece from our Spring 2020 issue. These readings are not intended to be definitive interpretations; when we read, we bring with us our own histories, experiences, and references, all of which guide our relationship to the work before us. It is possible, even probable, that the meanings our editors found in these pieces will be different from your own, and perhaps even different from the authors’ intentions. We hope that these close readings will demonstrate what we loved about these pieces, and encourage you to find things to love about them as well.

This week, Editor-in-Chief Sofia Montrone discusses “(46)" and "(47).”

Both of Patrick Redmond’s extraordinary poems hinge on the manipulative quality of images. In “(46)” there is the “mirrored ball” – a surface the distorts, even as it reflects – while in “(47)” the image of the slain deer is presented “through a filter of faded blue.” I am particularly struck by this detail about the filter, which, for me, conjures an entire, tacit context for the piece. I imagine one of those gaudy Instagram filters that overpaints an image with color and frames it with streaky lines in an attempt to make the photo, taken on a cellphone, seem more artistic and individual. My initial instinct, upon reading this piece, was to feel that the deer’s death was cheapened by the filter – transformed into an occasion for the brother to brag about his conquest. Now, I’m not so sure. As I have reread this poem over the intervening months, I have come to wonder if the brother’s intentional manipulation of the image is an attempt to imbue the death with a meaning beyond pure sport, and if the poem itself is an extension of this aspiration. Is the language of the poem not just another filter through which we confront the event? A way of controlling its image?

The images themselves are assertive and strange. I am impressed by the confidence with which Redmond describes the sensation of being “naked as a head/ penetrated by nails/ skimming the inner pitch of an attic” and the way “the light eats its dirt/ gathering on I-80, tectonic as milk and teeth.” The poems prowl forward, their movements graceful yet unexpected. Perhaps their most surprising turns come at the conclusions, which seem lift into a different register, “returning the focus to love.” Just as the “moth/ on the subway brings everyone to speak,” the poems invite us to follow a new, more hopeful train of thought, even past the page’s limit.

Read more of our Spring Issue here.

Close Reading Series: Spencer Grayson on "Newly, rendered, truly"

The Close Reading Series invites our board editors to write about a favorite piece from our Spring 2020 issue. These readings are not intended to be definitive interpretations; when we read, we bring with us our own histories, experiences, and references, all of which guide our relationship to the work before us. It is possible, even probable, that the meanings our editors found in these pieces will be different from your own, and perhaps even different from the authors’ intentions. We hope that these close readings will demonstrate what we loved about these pieces, and encourage you to find things to love about them as well.

This week, editor Spencer Grayson discusses “Newly, rendered, truly.”

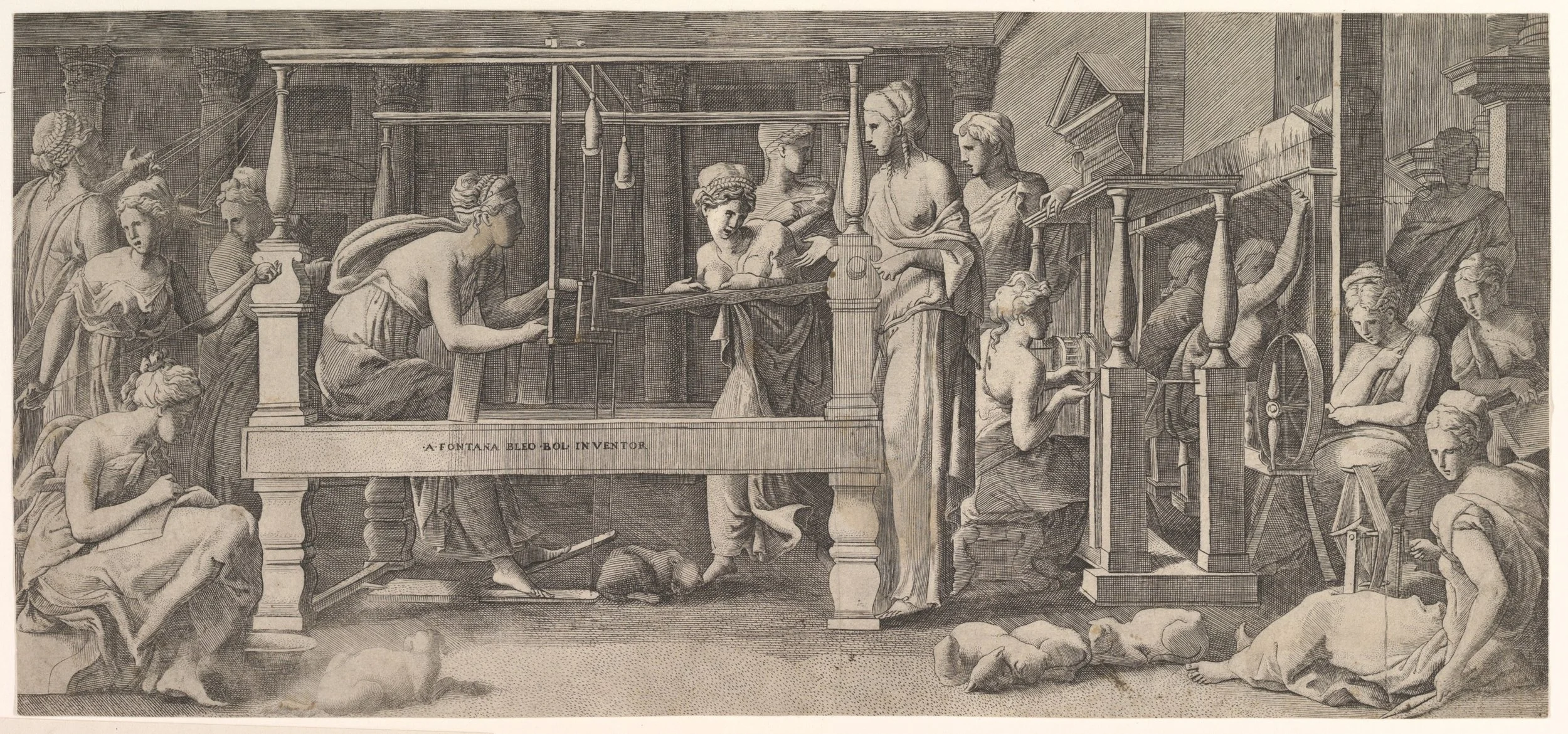

What I love about Kelly Hoffer’s “Newly, rendered, truly” is that, despite its sensual imagery—the speaker “lay[s]” their “pleasure across / the bed” and imagines being “dropped into a pool of cooling / lust”—its words operate less as signifiers for emotions and experiences than as meanings unto themselves. To me, the poem does not describe a scene of pleasure so much as it glories in the strangeness of poetry: how a word or phrase can mean nothing and yet make perfect sense. It’s for that reason that I think the first four lines are the best of the poem. Every time I reread this piece, I focus especially on those lines, noticing the rounded sounds, the echoing vowels.

Then I notice the enjambments, especially “ready for the swoon to fool / me, dropped,” “pool of cooling / lust,” and “a flower spools / sweet things beside.” When I read these enjambments aloud, their digraphs extend beyond the breath I took to read the full line. I become more conscious of taking my next breath in the middle of the following line. The poem forces an awareness of its rendering. You can’t read it smoothly, can’t ignore irregular shifts in breath and images that resist clarity.

Towards the end of the poem, the speaker asks: “if I give you a phrase will you sup- / ply the subject.” It is possible to supply a subject by offering a “deeper meaning” of Hoffer’s poem. “Newly, rendered, truly” is arguably concerned with the acts of spinning and weaving, writing itself: the language is formed of organic material, flowers “spool[ing]” phrases like thread and “sentence[s] seamed with stitching / nectar.” But, in response to the speaker, I would suggest that a subject and/or metatextual reading is not necessary to find that deeper meaning. Every sound in “Newly, rendered, truly” gives pause, and I keep returning to experience them all over again.

Read more of our Spring Issue here.

Close Reading Series: Maddie Woda on "The Crushing Pain of Existence"

The Close Reading Series invites our board editors to write about a favorite piece from our Spring 2020 issue. These readings are not intended to be definitive interpretations; when we read, we bring with us our own histories, experiences, and references, all of which guide our relationship to the work before us. It is possible, even probable, that the meanings our editors found in these pieces will be different from your own, and perhaps even different from the authors’ intentions. We hope that these close readings will demonstrate what we loved about these pieces, and encourage you to find things to love about them as well.

This week, editor Maddie Woda discusses "The Crushing Pain of Existence."

Zachary Schomburg's "The Crushing Pain of Existence" simultaneously makes me want to sigh with contentment and furiously weep, two excellent emotions to invoke in tandem. While I'm hesitant to throw the word "bittersweet" around lightly, this poem sits squarely in what I have to call a bittersweet tradition, in company with Liesel Mueller's "Late Hours" and Maggie Smith's "Good Bones." The language in "The Crushing Pain of Existence" is refreshingly simple, stripped of phrases my granddad would call "highfalutin" in his mild Appalachian accent. It is not stripped of sentiment, and this mild gooeyness might repel some readers--how many of us in poetry think we are post-sentiment, post-earnestness?--but I invite readers to lean into the sentimentality.

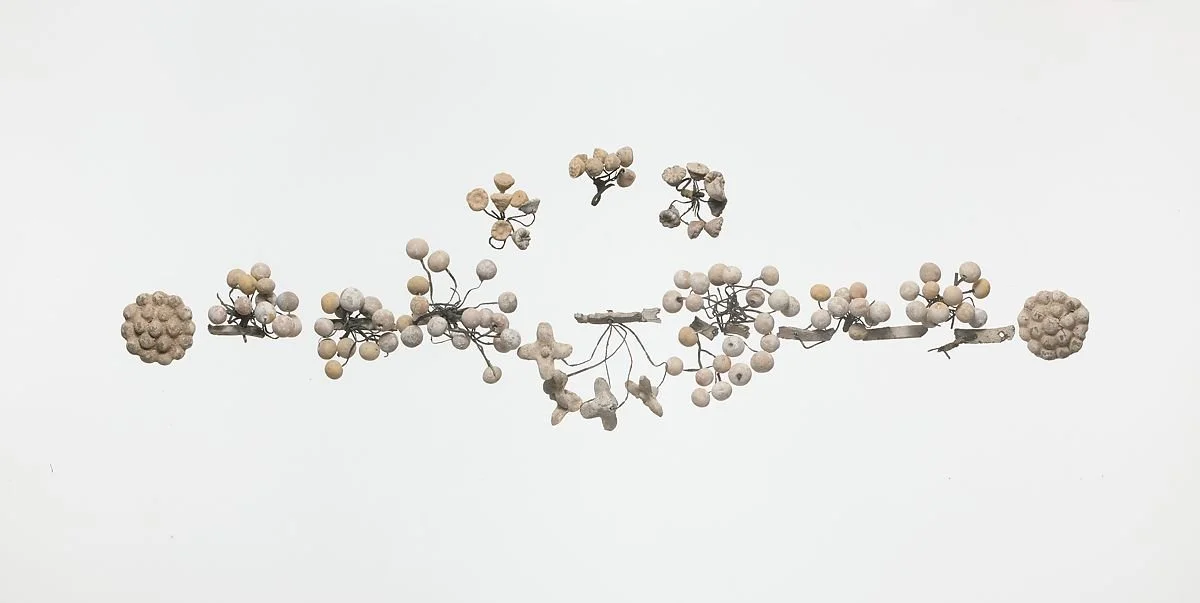

My roommate's long-distance boyfriend visited her at Columbia for the first time last year. After dinner, he plonked down in the nearest armchair, ready for conversation. My three other roommates and I froze. "Babe," my roommate nudged, "You know how your dad has a chair and everyone in your family avoids sitting in it? You're sitting in Maddie's chair." How many of us have experienced something similar, whether a roommate's chosen chair or a mug from which only your mother drinks her coffee? We anchor our lives in these small traditions. The first part of Schomburg's poem outlines this specific phenomenon, its simple resonance. The child in the poem distills her father's personality into this quirk, but it contains volumes about their relationship. My mind springs in all directions: he was home frequently enough to have a favorite spoon; perhaps each Sunday evening they ate ice cream together on the porch, father and child. He is a particular man but not fussy, a carpenter maybe, someone who measures and aligns. He favors touch of the five senses, his thumb imprinted on the cool metal of the spoon. Maybe the spoon was in his grandmother's silverware set, the last of the tarnished silver to get passed down. It is a symbol rife with meaning, but it is simple in its delivery of the symbol. It is the reader who imbues it with meaning, sentimental as that may be.

And then, of course, the volta-like shift, "I lived only to see how long I could outlive him." In a few words, the poem evokes the melancholy of loving a parent. You are expected to live life without them at some point, whether because of death or distance. Their personal traditions, which spoons they use for soup, are no longer acquired knowledge, no longer as obvious to you as the shirt they wear on Sundays. The last line is the most sentimental of the bunch, admittedly, but it saves itself from being cloying by shape-shifting. Every time I read it, it evolves into a new meaning. The flower is transient, but recurring? Its winter death is a part of life, its resurrection each spring equally expected? Somehow, it captures the tension I have always felt by being close with my parents. It is love with an expiration date: painful if they go first, tragic if I go first. It is wrapped up in responsibility, shame, devotion. I am a distorted reflection of them, and our love for one another is a wish.

Read more of our Spring Issue here.